|

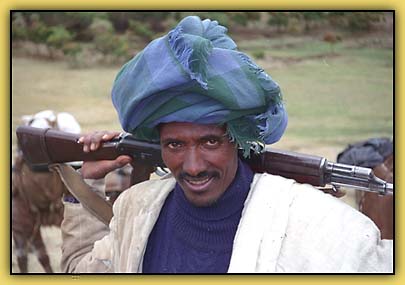

1983: A Country at War

On 28 May 1991, after years of brutal fighting, the government of Ethiopia

was finally toppled by a formidable coalition of rebel forces in which the

Tigray People's Liberation Front had played a leading role. When I went to

Axum in 1983, however, the TPLF was still a relatively small guerilla force

and the sacred city, although besieged, was still in government hands. Other

than myself, no foreigners had been there since 1974 when a team of British

archaeologists had been driven out by the revolution that had overthrown

Emperor Haile Selassie and that had installed one of Africa's bloodiest

dictators, Lieutenant Colonel Mengistu Haile Mariam, as Head of State.

Lamentably the free access that I was granted to Axum did not result from

any special enterprise or initiative of my own but from the fact that I was

working for Mengistu. As a result of a business deal that I was later

bitterly to regret I was engaged in 1983 in the production of a coffee-table

book about Ethiopia - a book that Mengistu's government had commissioned in

order to proclaim the underlying unity in the country's cultural diversity,

and to emphasize the ancient historical integrity of the political boundaries

that the rebels were trying so hard to redraw. It had been agreed before I

began work that there would be no overt promotion of the government's cause,

and it was written into my contract that no particular individuals (Mengistu

included) would be praised or vilified. Nevertheless I was under no illusions

about how the project was viewed by senior figures in the regime: they would

not have footed the bills, or permitted me to visit historic sites forbidden

to others, if they did not think that what I was doing would be helpful to

them.

Even so it was by no means easy for me to get to Axum. Intense rebel

activity along the main roads and around the sacred city itself meant that

driving was completely out of the question. The only option, therefore, was

to fly in. To this end - together with my wife and researcher Carol and my

photographer Duncan Willetts - I travelled first to Asmara (the regional

capital of Eritrea) where I hoped that it might be possible for us to hitch a

ride over the battle lines on one of the many military aircraft stationed

there.

Standing on a high and fertile plateau overlooking the fearsome deserts of

the Eritrean coastal strip, Asmara is a most attractive place with a markedly

Latin character- not surprising since it was first occupied by Italian forces

in 1889 and remained an Italian stronghold until the decolonization of

Eritrea (and its annexation by the Ethiopian state) in the 1950s.(8)

Everywhere we looked we saw gardens erupting with the colour of

bougainvillaea, flamboyants and jacaranda, while the warm, sunny air that

surrounded us had an unmistakable Mediterranean bouquet. There was also

another element that was hard to miss: the presence of large numbers of

Soviet and Cuban combat 'advisers' wearing camouflage fatigues and carrying

Kalashnikov assault rifles as they swaggered up and down the fragrant pastel

shaded boulevards.

The advice that these thickset men were giving to the Ethiopian army in

its campaign against Eritrean separatists did not, however, appear to us to

be very good. Asmara's hospitals were crammed to bursting point with

casualties of the war and the government of officials we met exuded an air of

pessimism and tension.

Our concerns were heightened a few nights later in the bar of Asmara's

rather splendid Ambasoira Hotel where we met two Zambian pilots who were on

temporary secondment to Ethiopian Airlines. They had thought that they were

going to be spending six months expanding their practical experience of

commercial flying. What they were actually doing, however, was ferrying

injured soldiers from the battle fronts in Tigray and Eritrea to the

hospitals in Asmara. They had tried to get the airline to release them from

this hazardous duty; on checking the small print of their contracts, however,

they had discovered that they were bound to do it.

After several weeks of almost continuous sorties in aged DC3 passenger

planes converted to carry wounded troops, the two pilots were shell-shocked,

shaky and embittered. They told us that they had both taken to the bottle to

drown their sorrows: 'I can't sleep at night unless I'm completely drunk,'

one of them confided. 'I keep getting these pictures passing through my mind

of the things that I've seen.' He went on to describe the teenage boy who,

that morning, had been dragged aboard his aircraft with his left foot blown

away by a mine, and another young soldier who had lost half his skull after a

mortar bomb had exploded nearby. 'The shrapnel wounds are the worst... people

with huge injuries in their backs, stomachs, faces... it's horrible...

sometimes the whole cabin is just swilling with blood and guts... we carry as

many as forty casualties at a time - way above the operating limits of a DC3,

but we have to take the risk, we can't just leave those people to die.'

They were required to fly three, sometimes four, missions each day, the

other pilot now added. In the past week he had been twice to Axum and on both

occasions his plane had been hit by machine gun fire. 'It's a very difficult

airport- a gravel runway surrounded by hills. The TPLF just sit up there and

take pot-shots at us as we land and take off. They're not fooled by the

Ethiopian Airlines livery. They know we're on military business...'

Overjoyed to have found some sympathetic non-Russian and non-Cuban

foreigners to share their woes with, the Zambians had not yet asked us what

we were doing in Ethiopia. They did so now, and seemed highly amused when we

replied that we were producing a coffee-table book for the government. We

then explained that we needed to get to Axum ourselves.

'Why?' they asked, dumbfounded.

'Well, because it's one of the oldest and most important archaeological

sites and because it was there that Ethiopian Christianity first got started.

It was the capital for hundreds of years. Our book's going to look really

sick without it.'

'We might be able to take you,' one of the pilots now suggested.

'What - you mean when you next go to pick up wounded?'

'No. You definitely wouldn't be allowed on those flights. But a delegation

of military top brass are supposed to be going there the day after tomorrow

to inspect the garrison. Maybe you could hitch a ride then. It would depend

on what sort of strings you're able to pull back in Addis. Why don't you

check it out?'

Return to Ethiopia Index

Initiation: 1986 |

A great mystery of the Bible |

1983: a country at war

Into Axum |

Palaces, catacombs and obelisks |

The sanctuary chapel

|

|